Archives

Table of Contents for Archive

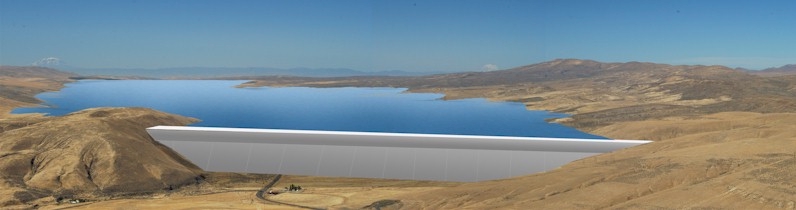

Lake Kachess project debated at water plan meeting

By TONY BUHR staff writer Ellensburg Daily Record Jun 23, 2017

YAKIMA — The Friends of Lake Kachess gave a presentation about their concerns and the costs of the Yakima Basin integrated water plan during a work group meeting Wednesday.

The 30-year, $4 billion Yakima Basin integrated water plan calls for habitat improvement and water storage in Kittitas, Yakima and Benton counties. Fully implemented, it would add more surface water storage capacity in the Yakima Basin, create fish passage at dams, acquire and protect private land and encourage water conservation.

The Friends of Lake Kachess oppose a proposal to place a pumping plant in Lake Kachess that would allow the lake to be drawn down an additional 200,000 acre-feet during droughts. Jay Schwartz, a member of the group and a professional data analyst, presented his findings during the meeting.

The Friends of Lake Kachess have attended and spoken at the Yakima work group meetings for months, but this week was the first time there was a more in-depth exchange involving both sides at a work group regular meeting.

The pump would not provide the benefit to farmers stated in a study completed by the Bureau of Reclamation, Schwartz said. The economic revenue generated from the crops grown would not justify the cost of the project, he said.

“It becomes a thing where do we want that incremental dollar to go and do we want to support irrigation in the Yakima basin or education or transportation?” he asked.

Roza irrigators are planning to pay for the full amount of the pumping plant, as well as maintenance and upkeep costs, Roza Irrigation District Manager Scott Revell said. No taxpayer dollars will be used in the implementation, he said.

The Friends of Lake Kachess have expressed frustration in the past over not being included in discussions involving the Yakima integrated water plan. Work Group Facilitator Ben Floyd said the presentation was an attempt to allow for more public comment.

Supporters of the integrated plan disagreed with Schwartz’s analysis of the project. Several farmers from the Roza Irrigation District spoke during the meeting about their struggles to keep crops alive during drought years.

“When I got into farming I didn’t know I was going to own an equipment company,” said Prosser farmer Dick Olsen. “We have built storage ponds and reservoirs wherever there is a spot where we could catch a little bit of moisture.”

Wapato farmer Ric Valicoff said farmers are trying all kinds of methods to modify the environment and collect as much moisture as possible. They have also spent millions of dollars shifting into crops that retain water.

“We all know we live in a desert with less than seven inches of rain and if it wasn’t for the snowpack we get we’d be a desert again,” Valicoff said.

CONCERNS AND FRUSTRATIONS

The Friends of Lake Kachess have said the proposed pumping plant would not provide the amount of water predicted by the Bureau of Reclamation, would have a devastating impact on the lake and not be cost effective for farmers.

According to Schwartz, the Bureau of Reclamation’s data shows that under adverse weather conditions Lake Kachess would never refill after being drawn down. Members of the integrated plan working group disagree.

A Bureau of Reclamation’s report has several climate conditions including moderate and less adverse conditions. Schwartz said according to a cost-benefit analysis of the integrated plan done by Washington State University economic professor Jonathan Yoder, the only condition under which the integrated plan provides an economic benefit to farmers would be adverse weather conditions.

The Yakima basin group has been working on a new economic impact study, and proponents say Schwartz’s analysis only looks the Kachess pumping plant by itself. The Yakima Integrated Plan is a series of projects that together will provide enough operational flexibility for the bureau to refill the lake, supporters have said.

Schwartz points out many of projects have a large price tag and would require funding by Congress, which has not happened.

According to the Bureau of Reclamation, the Cle Elum pool raise, which has been approved and is under construction, would provide enough flexibility within the Yakima River watershed to refill Lake Kachess.

Pumped Storage Projects

from Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

https://www.ferc.gov/industries/hydropower/gen-info/licensing/pump-storage.asp

January 23, 2017

Pumped storage projects move water between two reservoirs located at different elevations (i.e., an upper and lower reservoir) to store energy and generate electricity. Generally, when electricity demand is low (e.g., at night), excess electric generation capacity is used to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper reservoir. When electricity demand is high, the stored water is released from the upper reservoir to the lower reservoir through a turbine to generate electricity. Pumped storage projects are also capable of providing a range of ancillary services to support the integration of renewable resources and the reliable and efficient functioning of the electric grid. View Diagram of a Pumped Storage Project.

The Commission has authorized a total of 24 pumped storage projects that are constructed and in operation, with a total installed capacity of approximately 16,500 megawatts. Most of these projects were authorized more than 30 years ago. Recent Developments at FERC The Commission has seen an increase in the number of preliminary permit and license applications filed for pumped storage projects. Since the beginning of 2014, the Commission has issued licenses for three proposed pumped storage projects. Many of the recently proposed pumped storage projects can be classified as using a closed-loop system. We define:

- Closed-loop pumped storage as projects that are not continuously connected to a naturally flowing water feature; and

- Open-loop pumped storage as projects that are continuously connected to a naturally flowing water feature.

Differentiating between open- and closed-loop systems is helpful for illustrating trends in pumped storage project proposals, but project-specific impacts (rather than the open- vs. closed-loop classification) are the primary concern during the licensing process.

BENEFIT-COST ANALYSIS OF THE YAKIMA

BASIN INTEGRATED PLAN PROJECTS

REPORT TO THE WASHINGTON STATE LEGISLATURE

December 15 2014

Principal Investigators:

Jonathan Yoder, Project Lead and contact author

Director, State of Washington Water Research Center

Professor, School of Economic Sciences

Washington State University

yoder@wsu.edu

Jennifer Adam, Washington State University

Michael Brady, Washington State University

Joseph Cook, University of Washington

Stephen Katz, Washington State University

Click Here for Executive Summary

Criticism and response about the WRC study: Exchange between Malloch & Garrity and Yoder, The Water Report, May 2015. Full exchange (two articles and a pair of responses).

Proposed Congressional Legislation

S. 1694 sponsored by Cantwell

- Authorization of the Integrated Plan as Phase III of the YRB Water Enhancement Project

- Complete fish passage at Lake Cle Elum

- Nonfederal funding of Kachess drought relief pumping plant and transfer water from Keechlus to Kachess

- Make water transfers easier-facilitate water transfers between entities-cost share 50%

- Secretary of Interior-in coordination with Washington Sate and consultation with the Yakama Nation

- Secretary develop an intermediate development plan to update the Integrated Plan-commence no later than 10 years-final phase not later than 20 years

- The Secretary, State of Washington and Yakama Nation shall submit not later than 5 years a progress report to the House of REpresentative

- The report needs to include the amount of federal and nonfederal contributions received and spent

- The amount of water and costs associated with each storage project

- Yakama Nation gets water from Kachess if they agree to participate

- Power from Bonneville to Kachess project shall be paid by participants receiving benefits from the water

- Okay for surface storage for Rosa and Kittitas Irrigation Districts-Yakama Nation can choose to participate

- Feds cost share no more than 50%

- Other federal funds cannot be used for cost sharing

HR 4686 Yakima River Basin sponsored by Newhouse and Reichert

- Newhouse requested $100 million for Lake Cle Elum fish passage

- President’s budget-15.8 million for Yakima

Senate Passes Cantwell’s Yakima Water Bill, a National Model for Addressing Water Challenges through Collaboration

Sen. Cantwell’s Yakima Bill Will Help Restore Historic Fish Runs Blocked for More Than a Century and Support Drought Resilience for Ecosystems, Communities and Agriculture in the Yakima River Basin

The bill addresses long-standing water challenges in the state of Washington’s Yakima River Basin, which is one of the West’s most productive agricultural regions and once was one of the nation’s most productive salmon fisheries. Drought and growing demands on water historically led to water conflicts, lawsuits and environmental degradation in the basin. This bill ushers in a new era in water management in the basin by authorizing an integrated approach to balancing the needs of both humans and nature across the watershed through water conservation, ecosystem restoration and drought relief measures. In so doing, the bill seeks to bring water security for farmers, families and fish for years to come.

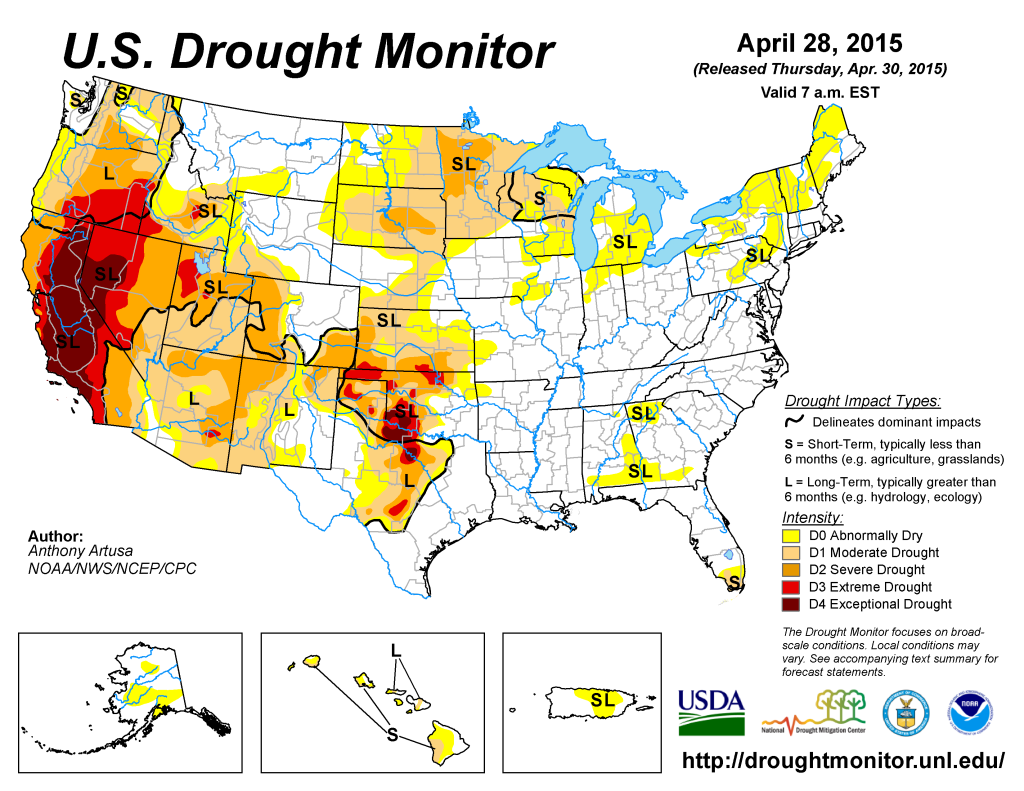

Unprecedented drought conditions in 2015 underscored the urgent need for enacting this bill. As in much of the West, last year’s drought brought record-breaking lows in snowpack, high heat, catastrophic wildfires, fish kills and restrictions in water use. The region is predicted to face continued drought and water supply challenges in the decades to come. These conditions could threaten ecosystems, including stream flows for fish, and the availability of water for crops and communities. That is why enactment of this bill is critical for the Yakima Basin.

The federal government has a responsibility to act now to prevent future impacts and costs in meeting its responsibilities in the basin, which include treaty and trust responsibilities to the Yakama Nation, protecting endangered species, managing public lands and managing extensive Bureau of Reclamation projects.

“We must act now to address the nation’s water challenges and the impacts of drought and climate change,” Sen. Cantwell said. “We have to put the days of fighting over water behind us and work together to find common ground to solve our collective water challenges. Yakima is leading the way.”

“We have a responsibility to protect Washington state’s unique natural resources, and I commend Senator Cantwell for her work to conserve water resources in the Yakima Basin for families, communities, farmers, and fish and wildlife,” said Sen. Murray. “As climate change continues to threaten our local communities, economy and iconic salmon runs, it’s critical that we continue working to protect our state’s precious water resources for future generations.”

“Trout Unlimited applauds Senator Cantwell’s tireless and consistent leadership to move S. 1694, the Yakima bill, through the legislative process including today’s critical vote by the full Senate,” said Lisa Pelly, director of the Washington Water Project of Trout Unlimited. “Her ability to work on a bipartisan basis with Senator Murkowski on the energy bill provides for new and important federal authorities necessary for moving forward on the collaborative efforts in the Yakima Basin that benefit fisheries, water supplies and local communities – creating a replicable model for communities across the West.”

“Sen. Cantwell has long been ahead of the curve in recognizing the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan as a model for 21st Century water management and ecosystem restoration. The Yakima bill embodies the kind of effective collaboration that will be needed to outpace threats from climate change,” said Michael Garrity, Puget Sound-Columbia Basin Director for American Rivers.

“It is exciting to see Sen. Maria Cantwell’s Yakima water enhancement bill move forward in support of one of our most important watersheds in Washington state,” said Tom Tebb, director of the Office of Columbia River with the Washington Department of Ecology. “This act is essential as we build on the success we’ve already achieved in the Yakima Basin to assure water security in times of drought and to prepare for climate change.”

Last July, Sen. Cantwell introduced the bill, which represents a hard-won compromise between conservation, recreation, agricultural and municipal interests as well as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the state of Washington and the federal government. Since the bill’s introduction, Sen. Cantwell has continued to work with these groups and community members to improve the bill. These efforts have resulted in a number of changes to the bill since its introduction, including:

(2) Changes to ensure broad public participation and oversight;

(3) Additional provisions supporting water conservation targets and water transfers;

(4) Additional provisions regarding studies to evaluate the feasibility, benefits and environmental impacts of projects in the basin; and

(5) Changes that clarify drought resilience activities to support irrigation districts and communities throughout the basin.

After a public hearing in November, the bill passed on a bipartisan basis out of the committee for consideration by the full Senate. The Yakima bill was included in the energy bill as an amendment, with other natural resources proposals. The bipartisan amendment was agreed to by a vote of 85 to 12. With the bill’s passage this week, the Yakima bill is one step closer to becoming a law.

Read the complete bill text.

Read the bill summary.

Read the summary of changes to the bill since it was introduced.

Read the frequently asked questions about the bill.

Read Sen. Cantwell’s opening statement from the July Yakima hearing.

Read Sen. Cantwell’s opening statement from the November Yakima mark-up.

Normandeau Study: “Trust but Verify”

Click Here for Executive Summary

For the complete Normandeau Report Click Here.

Time to Revive the Black Rock Reservoir Plan

By Don C. Brunell

June 26, 2015

Yakima Valley farmers have the same problem as their California counterparts: there just isn’t enough water for crops, migrating fish and people.

In California this year, an estimated 564,000 acres of prime cropland will be left unplanted because of the fourth straight year of drought. Economists at the University of California, Davis estimate the drought has caused $2.7 billion in economic losses and cost 18,000 farm workers their jobs.

The water shortage is so acute in California that Gov. Jerry Brown ordered a 25 percent reduction, which has even forced many expensive homeowners to rip out their manicured lawns and plant desert plants among sand and rocks.

There are similarities between California and Washington.

Just as the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers are the heart of California’s north central irrigation network, the Yakima River is the main artery flowing through one of our state’s prime growing regions.

With snowpack in the Cascades at a dismal 10 percent of normal, Yakima farmers are struggling to stretch available water supplies during the upcoming summer months when irrigation water is most needed. The situation has once again prompted state and federal officials to consider adding water storage capacity.

Considering that, it is time to dust off the Black Rock project, which, as originally conceived, would transfer spring runoff water from the Columbia River in central Washington uphill to a new reservoir east of Yakima.

It would be a mammoth undertaking. Under one proposal, the Black Rock Dam itself could be 750 feet high—taller than Hoover Dam on the Colorado River.

In 2008, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation determined that the Black Rock Reservoir would be too costly. The estimated cost then was about $5.69 billion, but it could potentially climb to as high as $7.7 billion. At the time, the Bureau reported that Black Rock would return 13 cents for every dollar spent to build and operate.

However, an independent impact study by the Yakima Basin Storage Alliance (YSBA) found that Black Rock would generate $8 billion in economic benefits from agriculture, tourism and construction jobs. YBSA figured an additional $3.5 billion would be generated in recreational opportunities alone, a factor not considered by the Bureau of Reclamation.

There is another reason to revive the plan. Over the last eight years, massive amounts of wind generation have come on line, which means, in addition to an irrigation lake, Black Rock could become a pumped storage facility generating hydropower from wind power.

Here is how it would work. Columbia River water would be pumped over the hill to Black Rock when wind electricity is abundant and costs are lower. The water could be sent back down the hill run through hydropower generating turbines and empty back into Columbia River at peak electricity demand periods.

A pumped storage project using wind-generated electricity would provide a storage battery for energy and would benefit fish, agriculture, municipal needs and economic stability while leaving a reliable water supply in the Yakima River.

Integrating wind and hydro works.

For example, Spain’s electric utility, Iberdrol, is using wind power to pump water up to storage reservoirs. When it rushed downhill through power turbines, Iberdrol is currently generating more electricity than Bonneville Dam—and more is on the way.

Using this same technology, Black Rock could become more than just an irrigation reservoir; it would ease the demand to divert water from the Yakima River for irrigation, leaving more water in the river, which would raise stream flows, which in turn would improve salmon and steelhead habitat.

It is a concept worth looking at that could make Black Rock economically feasible while providing everyone with much-needed additional fresh water.

Don C. Brunell is a business analyst, writer and columnist. He recently retired as president of the Association of Washington Business, the state’s oldest and largest business organization, and now lives in Vancouver. He can be contacted at theBrunells@msn.com.

Reusing Columbia’s Water Can Help Farmers and Fish

By Don C. Brunell

May 29, 2015

Traditionally, pumped storage is thought of in terms of power production, but sending water back into a reservoir such as Lake Roosevelt would not only increase power production, but the water could be available for irrigation, navigation and augmenting fish runs.

Since, northwest electric ratepayers already are charged for salmon recovery, perhaps some of those funds could be used to underwrite the costs of pumping.

Over the last few years, one of the remarkable successes is the record salmon returns to the Columbia River and its tributaries. Conversely, one of the biggest disappointments is low recovery of delta smelt in San Francisco Bay.

To protect the smelt, a federal court ordered that water be flushed into the San Francisco Bay – 1.4 trillion gallons since 2008. That was enough water to sustain 6.4 million drought-stricken Californians for six years. Yet a survey of young adult smelt in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta last fall yielded just eight fish, the lowest level since 1967.

Increasing river flows in the northwest to wash young salmon to sea has worked; nevertheless, once water goes down the river, it is gone. What if we could recycle that water in key parts of the Columbia River reservoir network?

It’s called “pumped storage.” It works in West Virginia and it could work in the Northwest.

In West Virginia, the Bath County project is the world’s largest pumped storage hydro system, producing about half the amount of electricity generated by the Grand Coulee Dam. During peak electrical demand, water flows through power generators draining into a lower reservoir and conversely, during periods of low demand, water is pumped back into an upper reservoir.

The difference in the price of electricity between low and peak usage makes the plant economically feasible and the plant operators have the option to power the pumps by substituting electricity from other sources, including wind and solar.

That concept may work at Grand Coulee Dam.

For example, during peak electrical demand, generators in Grand Coulee’s third powerhouse alone produce enough electricity to light Seattle. What about capturing that water below the dam and pumping it back into Lake Roosevelt during the late night and early morning hours when electricity demand is slack?

Traditionally, pumped storage is thought of in terms of power production, but sending water back into a reservoir such as Lake Roosevelt would not only increase power production, but the water could be available for irrigation, navigation and augmenting fish runs.

Since, northwest electric ratepayers already are charged for salmon recovery, perhaps some of those funds could be used to underwrite the costs of pumping.

It may be an approach to consider in the vast Columbia River system, which supports agriculture, salmon and produces 75 percent of our state’s electricity.

In 2000-01, when low stream flows in the Columbia system curtailed hydropower production, this region lost most of its aluminum smelters and the family-wage jobs that went with them as electricity was reallocated to household and commercial use.

Pumped storage could also avert water conflicts such as those occurring in California. As Californians suffer through their fourth year of record drought, hydropower’s share of the state’s total electricity supply has dropped from 18 percent to 12 percent. The deficit has been replaced by natural gas-fired generation, which adds to greenhouse gas emissions.

The University of California at Davis estimates the statewide economic cost of the 2014 drought totaled more $2.2 billion, including $810 million from lost crop revenue, $203 million from lost livestock and dairy revenue, and $454 million from the additional costs to pump groundwater to keep production going. The state has lost 428,000 acres of irrigated cropland and an estimated 17,000 part-time jobs.

Now, Gov. Brown has ordered a 25 percent reduction in water usage because there isn’t enough water for cities, farms and factories.

Rather than put ourselves in the same predicament as California, why not look at alternatives, such as pumped storage because when the pie is larger, there are fewer family fights over a smaller and smaller pie

Don C. Brunell is a business analyst, writer and columnist. He recently retired as president of the Association of Washington Business, the state’s oldest and largest business organization, and now lives in Vancouver. He can be contacted at theBrunells@msn.com.

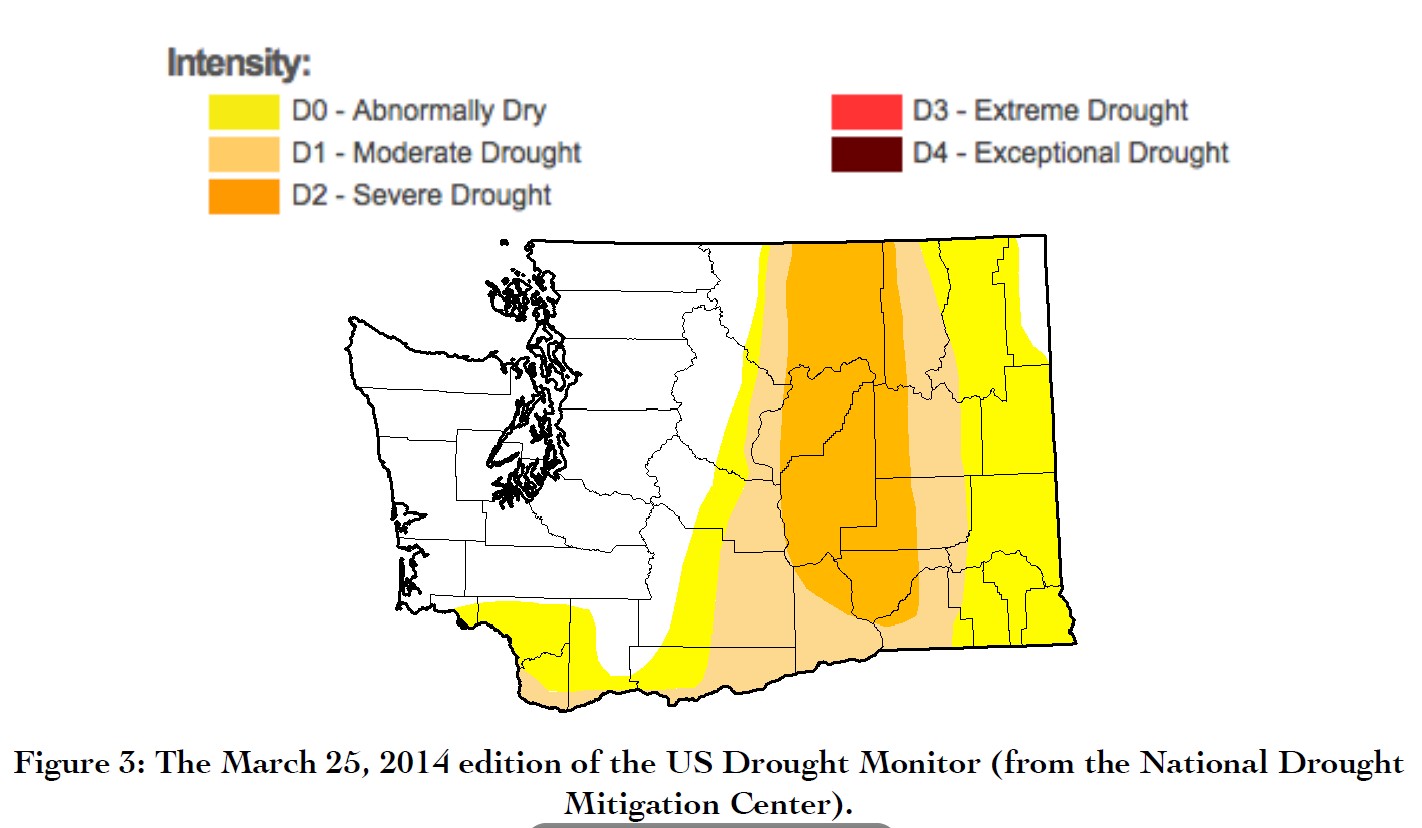

from State of Washington Department of Ecology

Statewide snowpack is above average for February – we will continue to monitor water supplies

Heavy rains and snow have virtually eliminated drought in most of Washington leaving the south-east corner of the state still in moderate drought according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Much of Washington’s water supply comes from snowpack accumulations which statewide are more than 100 percent of normal for this time of year. Forecasts for January thru March 2016 are for warmer, drier conditions as a result of El Niño. Forecasts for the April-September runoff period are within the normal range.

2015 Drought economic losses

An interim study of crop losses by the Washington Department of Agriculture estimates the economic impact of the 2015 drought on the state’s agricultural industry at more than $335 million. The total is expected to increase as the drought affected the quality and quantity of some Washington crops going to market in coming months.

Ecology committed $6.7 million in drought relief funding for 2015

The 2015 Legislature approved $16 million in drought relief funding for use in 2015 and 2016. As of December. 1, 2015, Ecology has committed $6.7 million of the total.

Click Here for more.

Attempts at Drought Relief in the Yakima Basin

from the Roza Irrigation District history page:

1977. This year was one of the most eventful in history of the Roza Irrigation District. Early predictions by the Bureau of Reclamation of only 6% of normal water supply for the district prompted many immediate actions by both the district and individual farmers. Many farmers with permanent crops faced total ruin if adequate water supplies could not be obtained. Expensive, deep wells were drilled, pumps were installed on drains, and lands were leased speculating on the water they might receive. Subsequent reallocations by Reclamation eventually brought the district to 70% of normal water supply, but for most farmers, it came too late. Investment in other water sources had already been made. The State and Federal governments made grants and low interest loans to many landowners to help defray some of the overwhelming costs of these emergency projects. The district, to help utilize some of the available funding, also established local improvement districts (LID’s). The district explored the possibility of acquiring Columbia River water. However, the financing of such a monumental project to provide a system for pumplift involved, the long conveyance system required, and the time to accomplish the task led to the plan’s demise.

Floating Pumps at Cle Elum Lake for Emergency Water Supply:

Constructed and briefly operated (tested) in 1977; suffered fire damage, sunk, and then disassembled in September, 1988.

Bumping Lake Enlargement:

In 1987, a Policy Group was structured to provide a forum for oversight of the Yakima River Basin Water Enhancement Project. Comprehensive legislation was introduced in the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives providing for the development of a 400,000 acre-foot capacity Bumping Lake Enlargement and associated actions such as water conservation and improved fishery habitat. However, this effort was terminated in September, 1988, and Yakima River Basin Adjudicated proceeded.

Yakima River Storage Study:

In 2004, the Yakima River Storage Study was authorized and funded The storage study evaluated the options of enlarging Bumping Lake, creating a Wymer Reservoir and pumping water from the Columbia River during winter months. Bumping Lake Enlargement and creating Wymer Reservoir were not considered viable and were eliminated. The stored water in the proposed reservoir would be used to irrigate Roza and Sunnyside Irrigation Districts. The water removed annually from the Yakima River would remain to be managed and used to benefit the Yakima Basin. In 2008 the Bureau of Reclamation chose the no-action alternative which eliminated the Columbia River pump-storage project which terminated the possibility of bringing Columbia River water to the Yakima Basin.

Work Group:

In 2009, the Department of Ecology and the Bureau of Reclamation formed a Work Group to develop the Yakima River Basin Integrated Water Resource Management Plan. The plan was developed to provide benefits to all water related programs in the Yakima Basin, a surface water storage plan that included expansion of Bumping Lake, building a Wymer reservoir, pumping water from lake Kachess, raising the level of Lake Cle Elum 3 feet, and beginning an appraisal of transferring water from the Columbia River. The storage plan is to be completed in 30 years.

Study Continues:

As of 2015, studies are continuing on the storage projects to evaluate the feasibility of Bumping, Wymer, and Kachess. The extension of a permit to access water from the Columbia River as part of the Integrated Plan has been extended. Even if all proposed storage projects are completed the Yakima Basin will continue to have insufficient water needed for fish, agriculture, and economic growth.

Lake Keechelus

Click Here for YBSA’s comments on the DEIS prepared for the KKC and KDRPP Projects.

Basinwide Yakima water plan aims for long-range solution

MIKE JOHNSTON | Daily Record senior writer – May 18, 2015

A group of people working on a long-term plan for the Yakima River basin say this past winter — with little snow, more rain and now, drought conditions — likely is a taste of what’s to come. “We’ve never had a winter like this,” Kittitas Reclamation District Board member Urban Eberhart said. “The snowpack and the water we need from it just wasn’t there. We don’t have the capacity, right now, to capture all the rain that fell this winter; it flowed through the system.” The worry, Eberhart added, is this could be the beginning of an early string of low-snow winters long before the water-saving projects are hoped to be on line.

Concerns about climate change and drought are one reason Eberhart and a diverse group of other people have been working on a 30-year, $4 billion to $5 billion Yakima River basin integrated plan. They said the plan is a wide-ranging, water-supply boosting, fish-habitat enhancing and ecosystem improving schedule of projects that are cumulative in their overall impact. No one project does it all, but it works when they’re operating as a package, together, they said.

The projects have the daunting goal of keeping basin water supplies adequate and stable far into the future for all uses — fish and wildlife habitat, cities and rural communities, irrigated agriculture, recreation and more. One target is to maintain, at a minimum, 70 percent of the water supply that irrigation entities are entitled to every year from the Yakima River system. Irrigators say that’s the bare minimum needed to get by in the growing season.

Come together

The plan was formed 2009 through 2012 by a work group of all major water interests in the 6,000-square-mile, three-county basin. It’s the first-ever agreement in nearly 40 years receiving wide support among diverse and sometimes oppositional interests. During a Daily Record editorial board meeting earlier this month, representatives from environmental groups, local governments, state wildlife agencies, irrigation districts, agricultural producers and the Yakama Nation discussed the long-range plan and this year’s drought. “This not about how we can get new supplies of water; there is no new water available in the basin,” said Steven Malloch, representing the environmental advocacy group American Rivers. “This is all about better managing of the finite water we have, getting the best and widest use for everyone.”

Group members pointed to the need for the plan in light of climate change models showing a forecast of shrinking winter snowpacks in the central Cascades and more rain. Water users in the Yakima River basin rely every year on a slowly melting mountain snowpack to supply a third to a half of what they need. The remainder of the annual demand, hopefully, is supplied by a system of five, large, Cascade mountain reservoirs, three of which are in Upper Kittitas County.

Another factor is the legal reality that the amount of water that water-right holders have a right to draw and use from the Yakima River system exceeds the amount of water the river system produces each year. The huge watershed, basin and river system is over-appropriated, and the group agrees that the water the basin does receive must be better managed, stored, conserved and reused.

Urgency

Eberhart said the hope is that this winter’s scant snow is only an anomaly, and cold, snow-laden winters will return next year. This year’s winter set records for the lowest amount of snow in Cascades, he said. The group agreed it’s often a challenge to get the wider public’s attention about the long-standing need for basin water projects. “The larger water issues we’re facing in the basin, well, they can be just plain hard for people to understand without the context of the overall picture,” Malloch said. Eberhart tries to explain the basin’s over-appropriated water and changing climate trends whenever he can, he said, and that “this isn’t hype; it’s really going on right now,” and can be seen in dramatic cuts in water allocations to basin irrigators.

Capture the rain

Additional water storage capacity in the basin, Malloch said, can help capture rain runoff from the predicted weather patterns prompted by climate change, water that would have flowed through the river system. Tom Ring, a Yakama Nation hydrogeologist, said federal authorization for some of the plan’s projects have already been granted but need funding. State government in 2013 approved more than $132 million to kick-start early projects, including a purchase of 50,000 acres of private timberland in the Teanaway River drainage basin in Upper County, an important watershed area at the Yakima River’s headwaters that requires protection.

Another plan-related project in 2013-2014 was turning open irrigation ditches into water-saving, pressurized irrigation piping in the Manastash Creek area that also assisted the Kittitas County Conservation District. “Those coming together to put together this plan is unprecedented in the basin’s history,” Ring said. Having more stable water supplies that can be relied on year-to-year and a way to get fish through the basin’s dams, means rejuvenation of migratory and resident fish runs, said Jeff Tayer, representing the state Fish and Wildlife Department.

All together

Scott Revell, manager of the Roza Irrigation District, said the plan doesn’t look at any one project, but each project works in sync with the others to make for a more reliable water supply. Malloch said there is no way to improve water supply management in the basin without the support of everyone in the work group. “The plan isn’t perfect, not everyone likes every part of it, but we’ve laid aside our issues to understand the issues faced by others. We can only make this work by cooperation,” he said.

Kittitas County Commissioner Paul Jewell said public understanding of the basin integrated plan is creating challenges when understanding isn’t there. “The reality is this is all for the greater good,” Jewell said. “It’s a tremendous political hurdle.”

Not all pleased

Malloch said not everyone will be pleased as the plan’s separate projects come up for environmental review, design, engineering and construction in the coming years. Plans for Bumping Lake and Lake Kachess have met resistance from those with cabins and homes nearby, for example. Malloch said study after study shows more changes in water delivery and district and on-farm use are needed to conserve water, making more available to all. He said the studies also show conservation alone won’t stabilize water supplies, that new water storage reservoirs are needed. Eberhart said he sees the plan as essential to allow life to go on in the Yakima River basin for generations to come. “We came up with a way we could all survive,” Eberhart said.

Recent projects update-

Raise Lake Cle Elum reservoir pool three feet

The final environmental impact statement has been completed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the state Department of Ecology that examines the basin integrated plan project to increase water in the Lake Cle Elum reservoir in Upper Kittitas County by raising its capacity by three feet. Copies of the report may be obtained by calling 509-575-5848, Ext. 232, or at http://www.usbr.gov/pn/programs/eis/cleelumraise/index.html.

Lake Kachess projects

A call for a second round of public comments is underway by the bureau and Ecology Department on a pipeline project from Lake Keechelus reservoir in Upper County to the high-capacity Lake Kachess reservoir, with an emergency drought pumping system also at Kachess. The deadline for public comments to be received is June 15, and can be submitted to kkbt@usbr.gov, by mail to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Attn: Ms. Candace McKinley, environmental program manager,1917 Marsh Road, Yakima, WA, 98901; by telephone to 509-575-5848, Ext. 603.

Yakima River basin integrated plan-

Major elements:

Fish passage: Provide fish passage at every major Yakima River basin dam (preliminary work may begin this year at Lake Cle Elum reservoir). Structural and operational changes: Promote operational efficiency and flexibility at existing in-basin facilities (the Keechelus and Kachess reservoir projects included).

Surface water storage expansion: Develop an additional 450,000 acre-feet of additional water storage for supporting instream and out-of-stream uses in the Yakima River basin (this includes more water in Lake Cle Elum and a new reservoir in the Yakima River Canyon southeast of Ellensburg).

Groundwater storage: Recharge underground soil or rock formations with surface water for storage and recovery for future use.

Habitat/watershed protection and enhancement: Enhance critical habitat for migrating and resident fish and wildlife.

Enhanced water conservation: Aggressively implement water-use efficiency measures and projects involving irrigation entities and other water users to improve water supply available for instream flow support in critical stream reaches.

Market-driven reallocation: Create conditions within which water banks can facilitate the sale or lease of water between willing parties on a temporary or permanent basis.

Three-phase project over 30 years-

Phase 1 (current projects in a 10-year period)

Initial phase projects:

Lake Kachess reservoir drought relief pumping plant – $205 million; fish passage at Lake Cle Elum reservoir – $87 million; three-foot rise in the Lake Cle Elum reservoir capacity – $18 million; and the $159 million Lake Keechelus reservoir to Lake Kachess reservoir pipeline to fill the larger-capacity Lake Kachess with Lake Keechelus water.

Undertake $85 million in projects to help agricultural producers and irrigation districts conserve water by using less, with the goal to make available about one-half of the 170,000 acre-feet of conserved water envisioned by the plan.

$100 million in floodplain and tributary habitat restoration projects and acquisitions, $90 million for additional fish passage projects, $6 million in aquifer storage and recovery projects, and $500,000 for fostering water banking and exchange programs.

Attempts to attain Wild and Scenic River designations for some headwater stream reaches will also be advanced during the initial phase, beginning with portions of the upper Cle Elum River system planned is a cost of $15 million for feasibility studies and prepare an environmental impact statement examining the construction of one the two, new large storage facilities called for in the plan.

Updated New Storage is the Only Solution for the Yakima River Basin: Comparison of Black Rock and the Integrated Plan Storage

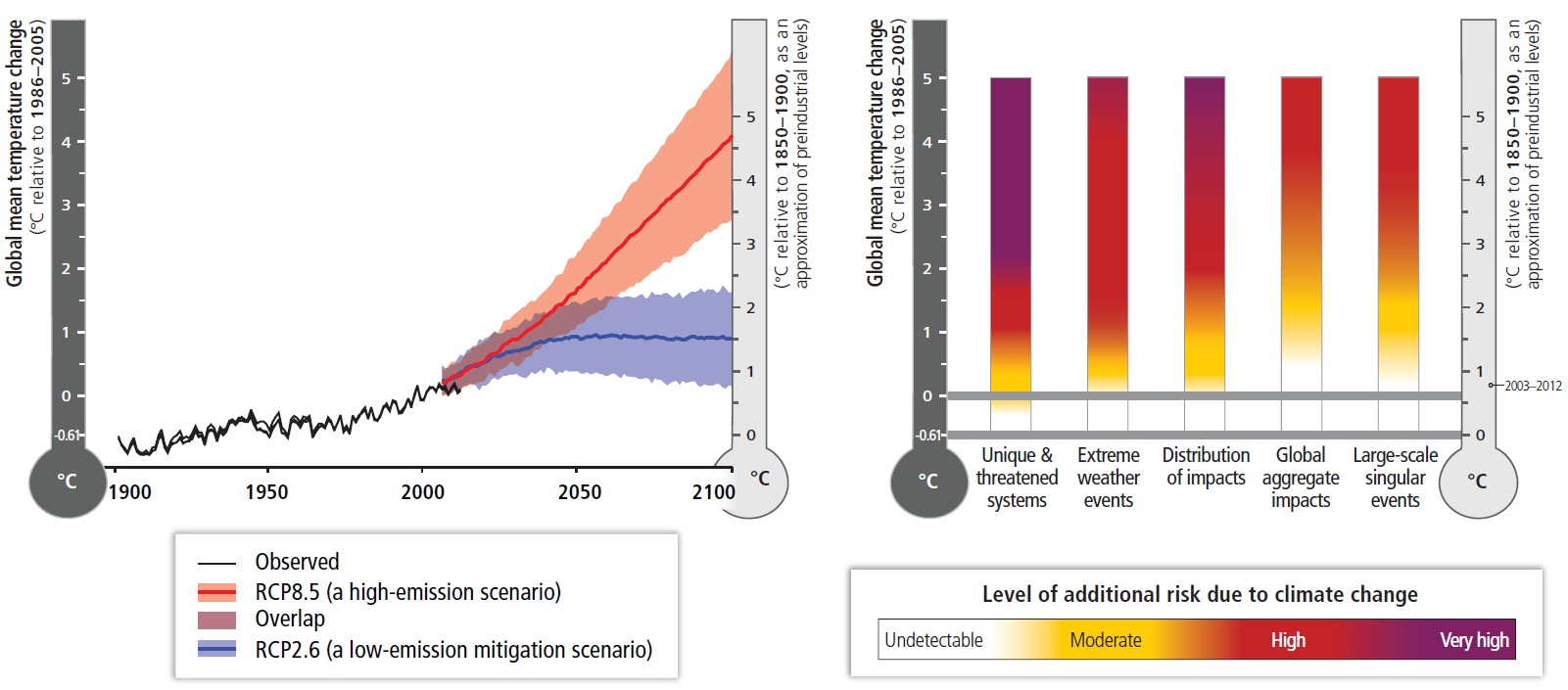

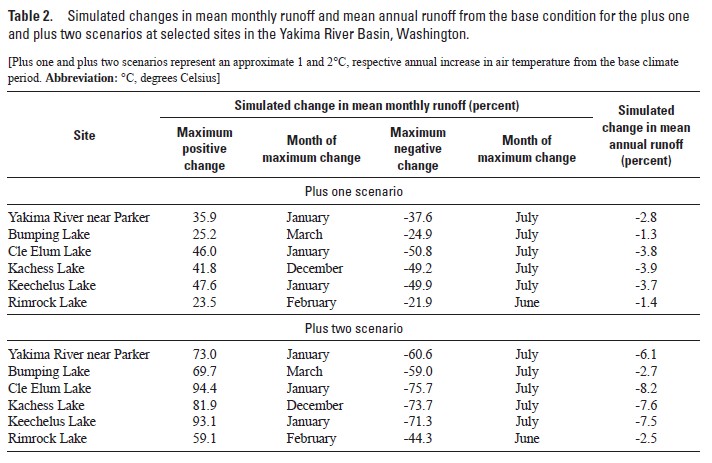

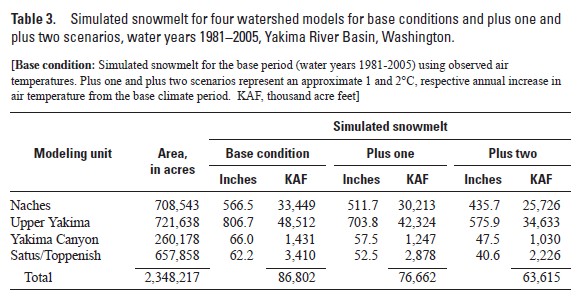

The report describes the future potential climate change that may occur in the Yakima River Basin. Tables 2 & 3 below show the possible changes that would effect instream flow and out of stream water usage. All watershed plans should consider the lesser amount of water runoff and snow melt conditions in the Basin.

Click on Effects of Potential Future Warming on Runoff in Yakima Basin for the full report.

Click on Effects of Potential Future Warming on Runoff in Yakima Basin for the full report.

Yakima River Above Sunnyside Dam

Yakima River Above Sunnyside Dam  Yakima River at Toppenish

Yakima River at Toppenish  Yakima River at Prosser

Yakima River at Prosser

Facts Pertaining to the Yakima River Basin Under present physical conditions in the Yakima River Basin there is an insufficient supply of ground and surface water to satisfy the present needs of the basin. The future competition for water among municipal, domestic, industrial, agricultural, and instream water interests in the Yakima River Basin will be intensified by continued population growth, and by changes in climate and precipitation patterns. The Yakima River The Yakima River originates at the outlet of Lake Keechelus and runs for 214 miles in a southeasterly direction to its confluence with the Columbia River at Richland. With its tributaries, the Yakima River drains about 6,150 square miles or 4 million acres. The headwaters of the Yakima Subbasin originate in the high Cascade Mountains, with numerous tributaries draining subalpine regions within the Snoqualmie National Forest and the Alpine Lakes, Norse Peak, and William O. Douglas Wilderness areas. Major tributaries include the Kachess, Cle Elum and Teanaway rivers in the northern part of the subbasin. The Swauk, Teneum, Umtanum, Manastash, and Wenas creeks drain into the upper and middle Yakima River. The Naches River in the west is formed by the confluence of the Bumping and Little Naches Rivers. Tributaries of the Naches include the Tieton River and Rattlesnake and Cowiche creeks. Ahtanum, Toppenish, and Satus creeks join the Yakima in the lower subbasin from the west. Storage Six major reservoirs are located in the subbasin and form the storage component of the federal Yakima Project, managed by the USBR. These six reservoirs are Keechelus Lake, Kachess Lake, Cle Elum Lake, Rimrock Lake, Bumping Lake, and Clear Lake. Total storage capacity of all reservoirs is approximately 1.07 million acre/feet. With the exception of Rimrock and Clear Lake, all reservoirs were natural lakes, formed during the period of glaciation, prior to the construction of dams near their respective outlets. Approximately 3 million acre/feet are needed in the Yakima Basin annually. Precipitation Virtually all of the streams in the subbasin originate at higher elevations where annual precipitation is 30 inches or more. The rainy season in the valleys occurs during November through January when about half the annual precipitation occurs. Snowfall in the valleys ranges from 20 to 25 inches and from 75 inches at 2,500 feet to over 500 inches at the summit of the Cascades. This mountain snow pack provides most of the water for irrigated agriculture and streamflow. Property Ownership Private ownership totals 32 percent or over 1.2 million acres of the 4 million acres in the Yakima Subbasin. The single largest landowner is the U.S government with 1.5 million acres or 38 percent of the land area. Most of the federal land is within the Wenatchee National Forest. Other large federal land holding include the U.S. Army Yakima Training (YTC) Center, the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, and Bureau of Land Management lands (BLM). Other public ownership (state, county, and local governments) total over 400,000 acres. The YN Reservation covers 1,371,918 acres in southern Yakima County and a smaller part of Klickitat County. The YN and its members have over 880,000 acres held in trust; only a small portion is deeded land. The Future With climate change estimating a reduction in snow pack the ability to provide the additional water needed annually in the Yakima Basin for fish, agriculture, and residential, municipal and industrial use needs to be addressed.

Bumping Lake Reservoir Bumping Lake Reservoir

Bumping Lake Reservoir Bumping Lake Reservoir

Lake Cle Elum Reservoir Lake Kachees Reservoir

Lake Cle Elum Reservoir Lake Kachees Reservoir

Lake Keechelus Reservoir Lake Keechelus Reservoir

Lake Keechelus Reservoir Lake Keechelus Reservoir  Rimrock Reservoir

Rimrock Reservoir

Yakima Basin Storage Alliance

The Storage Component of the Integrated Plan Must Be Evaluated Immediately to Assure Sufficient Water for the Yakima Basin

The Yakima Basin Storage Alliance (YBSA) is a local “grassroots organization” formed to raise the awareness of the dependence of our Yakima River basin economy and environment on a reliable surface water supply and the need for additional stored water. YBSA is in a unique position in the Workgroup not being affiliated with any specific entity, agency or interest group. YBSA is focused solely on the challenge of an adequate and reliable water supply for the future in concert with our environmental and cultural values. In March 2012, a Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement was completed in which two plan alternatives were evaluated; a No Action Alternative and the Integrated Plan. The Integrated Plan consisting of a surface water storage element and six complementary elements was selected as the Preferred Alternative to move forward for Congressional and State legislative authorization and funding for implementation.

Bob Tuck Salmon Walk on the American River

Life Cycle of Spring Chinook on the Cle Elum River

Sockeye Above Lake Cle Elum

Why YBSA believes more water is required for the Integrated Plan YBSA supports the Integrated Plan because it is the best vehicle to solve our long term water needs. YBSA has been the only advocate for significantly increased water storage for the Integrated Plan. As such we are compelled to explain why. Those reasons include instream flows, Irrigation droughts, and Climate Change. Click Here for Full Document

Summary of Reliability of the Water Supply for the Yakima Basin

(Click Here for full article)

Introduction

Yakima Basin Storage Alliance and why this document.

(see below for the “Reliability of the Water Supply for theYakimaBasin” document)

Background

The five major reservoirs of the Yakima Project with a total capacity of 1,045,000 acre/feet provide water for irrigation, fish and wildlife, flood control, and recreation. The sixth reservoir is the snowpack in the higher elevations of the east side of the Cascade Range which is critical to providing the water needed in theYakimaRiver Basin. TheAcquavella Adjudication Courtmandated that the rights of the Yakama Nation to instream flow for anadromous fishery are time immemorial and senior to all other rights within theYakimaBasin. Beginning in 1995, following the passage of the Act of October 31, 1994 (Title XII), and the instream target flows at Sunnyside and Prosser dams, the total demand placed against the Total Water Supply Available (TWSA) in a normal water year was about 2.7 million acre/feet.

(see below for the “Reliability of the Water Supply for theYakimaBasin” document pages 1-4)

Climate Change

Studies by the University of Washington working with United State Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies using three climate change scenarios, less, moderately, and more adverse spring and summer runoff is expected to decrease (ranging from 12 to 71%) and fall and winter runoff is expected to increase (ranging from 4 to 74%). The shift in runoff quantity and timing would cause significant risks to water supply.

(see below for the “Reliability of the Water Supply for theYakimaBasin” document pages 4-5)

Climate Change Impacts

Total Water Supply Available Irrigation Proration Level Insteam Flows For the Integrated Plan without climate change there are four dry years (1993, 1994, 2001, and 2005). With the climate change scenarios the number of dry years increases, the Total Water Supply Available decreases, and the 70 percent irrigation proration level criteria of the Integrated Plan may not be met in some years as follows:

- Less Adverse: Seven dry years with the irrigation proration level at 70 percent for each year.

- Moderately Adverse: Fourteen dry years and the 70 percent irrigation proration level criteria are violated in every year.

- More Adverse: 24 dry years and the 70 percent irrigation proration criteria is violated in 22 of these years.

(see below for the “Reliability of the Water Supply for theYakimaBasin” document pages 5-7; figures 1 & 2)

Carryover Storage and Reservoir Refill

Table 3 provides a summary of the number of years of the 25 year period (1981-2005) that the three major water storage projects of the IP refill to the indicated capacity.

(see below for the “Reliability of the Water Supply for theYakimaBasin” document page 8; figure 3)

Conclusions

With the time immemorial Treaty right of the Yakama Nation for instream flows to sustain anadromous fisheries being senior to all other water rights, and with climate change having the potential to seriously affect the reliability of in-basin stored water supplies, we are faced with the reality that a Columbia River pump exchange is the only source of “new water” to supplement our over-appropriated Yakima River system.

(see below for the “Reliability of the Water Supply for theYakimaBasin” document page 9)

Use the link below to get the full Reliability of the Water Supply for the Yakima Basin document. Reliability of the Water Supply for the Yakima Basin

Yakima Basin Storage Alliance Goals To launch a grass-root campaign designed to educate and raise the awareness about the need for additional water for fish and irrigated agriculture including its relationship with Washington State communities and economies. To provide evidence demonstrating why the Yakima Basin desperately needs increased storage to address climate change and groundwater usage effects on the Yakima River. To illustrate that the Yakima Basin’s economies are in jeopardy if we do not increase water storage for the Yakima Basin. To become a resource and catalysts for storage activism, both locally and statewide. To actively investigate, identify, assess, and promote storage solutions. To become the umbrella organization for Yakima Basin storage supporters that will result in increased storage to benefit irrigated agriculture, instream flows, salmon recovery, Yakima River ecology, and Yakima Basin communities.  Yakima Basin Storage Alliance’s (YBSA) basic message (objective) has been “The Need for a Reliable Water Supply for the Future”.

Yakima Basin Storage Alliance’s (YBSA) basic message (objective) has been “The Need for a Reliable Water Supply for the Future”.  To more effectively meet the need for water storage and stabilization, YBSA urges that the Columbia River Pumped Storage option be developed as the project to address the long term need for water. YBSA believes that funding for a study of the Columbia Pumped Storage option should be made a priority and the study should include a pumped storage electricity production element. With the abundance of wind an water available in the spring a Wind Integration/Pumped Storage project would provide an opportunity for private-public involvement.

To more effectively meet the need for water storage and stabilization, YBSA urges that the Columbia River Pumped Storage option be developed as the project to address the long term need for water. YBSA believes that funding for a study of the Columbia Pumped Storage option should be made a priority and the study should include a pumped storage electricity production element. With the abundance of wind an water available in the spring a Wind Integration/Pumped Storage project would provide an opportunity for private-public involvement.

Video from Cle Elum River The Yakama Nation reintroduced Sockeye Salmon in Lake Cle Elum. Two types of Sockeye Stock, Wenatchee and Okanogam, were caught in an adult fish trap in Priest Rapids Dam and trucked to Lake Cle Elum and released in 2010. The video link that follows shows the Sockeye spawning in the Cle Elum River watershed above Lake Cle Elum.

Bob Tuck Salmon Walk on the American River

Prior to Euro-American development, there was one huge salmon run with the largest number of salmon returning during the summer. Unfortunately, water development projects on the tributaries of the Yakima, as well as the mainstem, have eliminated those runs that migrated during the summer, or utilized habitat in areas that are now unsuitable because of floodplain habitat alterations or water temperature. Thus we are left with species and runs whose migration timing and habitat areas are compatible with our water development. Fall Chinook migrate, spawn, and rear in the Lower Yakima River during times of the year when water temperatures are not excessive. Spring Chinook avoid high water temperatures by migrating through the lower river during the spring, and spawn and rear in the upper watershed where water temperatures are not normally a concern. Steelhead hold in the Columbia River and do not enter the Yakima River until water temperatures have moderated in the early fall, and complete their migration in the spring. Historic Fish Runs in the Yakima Basin Video

Thus we are left with species and runs whose migration timing and habitat areas are compatible with our water development. Fall Chinook migrate, spawn, and rear in the Lower Yakima River during times of the year when water temperatures are not excessive. Spring Chinook avoid high water temperatures by migrating through the lower river during the spring, and spawn and rear in the upper watershed where water temperatures are not normally a concern. Steelhead hold in the Columbia River and do not enter the Yakima River until water temperatures have moderated in the early fall, and complete their migration in the spring. Historic Fish Runs in the Yakima Basin Video  Each species and run has different habitat requirements. Spring Chinook spawn in smaller streams, such as the upper Yakima, Cle Elum, Teanaway, American and Little Naches rivers. Juvenile spring Chinook spend 1 year in freshwater and then migrate to the ocean. Fall Chinook are big river spawners; the Columbia and Snake rivers and the lower Yakima River. Juvenile fall Chinook only rear in fresh water for approximately 3 months and then go to the ocean; which means their juveniles migrate during late spring and early summer, thus avoiding high water temperatures in most years. Summer Chinook are in between, literally; they return during the summer and exhibit life cycles similar to both fall Chinook and spring Chinook. Summer Chinook spawn primarily in the Wenatchee and Okanogan Rivers in Washington, as well as the Snake River drainage in Idaho. Washington juvenile summer Chinook migrate to the ocean during the spring and summer of their first year, much as fall Chinook, while Snake River summer Chinook behave more like spring Chinook, in that the juveniles rear in freshwater for a full year before migrating to the ocean. Historically, The Chinook run in the Columbia River was one long silvery parade, beginning in February in the Lower Columbia River and lasting into November. Summer Chinook constituted the majority of this enormous bounty. Now we have 3 much-reduced humps on the graph representing small numbers of salmon in the spring, summer, and fall migration periods, instead of one big continuous curve. Summer Chinook, along with sockeye and coho are extinct in the Yakima Basin. The Yakama Nation is in the process of re-introducing coho and sockeye. In 2010, approximately 13,000 Spring Chinook were counted at Prosser Dam, along with several thousand fall Chinook, coho, and steelhead. A female Salmon digs a redd, or nest, in the gravel in the bottom of the river to deposit her eggs. When she is ready to lay a portion of her eggs, she releases pheromones to attract the male. Once the male joins her in the bottom of the redd, she releases some of her eggs and the male fertilizes them.

Each species and run has different habitat requirements. Spring Chinook spawn in smaller streams, such as the upper Yakima, Cle Elum, Teanaway, American and Little Naches rivers. Juvenile spring Chinook spend 1 year in freshwater and then migrate to the ocean. Fall Chinook are big river spawners; the Columbia and Snake rivers and the lower Yakima River. Juvenile fall Chinook only rear in fresh water for approximately 3 months and then go to the ocean; which means their juveniles migrate during late spring and early summer, thus avoiding high water temperatures in most years. Summer Chinook are in between, literally; they return during the summer and exhibit life cycles similar to both fall Chinook and spring Chinook. Summer Chinook spawn primarily in the Wenatchee and Okanogan Rivers in Washington, as well as the Snake River drainage in Idaho. Washington juvenile summer Chinook migrate to the ocean during the spring and summer of their first year, much as fall Chinook, while Snake River summer Chinook behave more like spring Chinook, in that the juveniles rear in freshwater for a full year before migrating to the ocean. Historically, The Chinook run in the Columbia River was one long silvery parade, beginning in February in the Lower Columbia River and lasting into November. Summer Chinook constituted the majority of this enormous bounty. Now we have 3 much-reduced humps on the graph representing small numbers of salmon in the spring, summer, and fall migration periods, instead of one big continuous curve. Summer Chinook, along with sockeye and coho are extinct in the Yakima Basin. The Yakama Nation is in the process of re-introducing coho and sockeye. In 2010, approximately 13,000 Spring Chinook were counted at Prosser Dam, along with several thousand fall Chinook, coho, and steelhead. A female Salmon digs a redd, or nest, in the gravel in the bottom of the river to deposit her eggs. When she is ready to lay a portion of her eggs, she releases pheromones to attract the male. Once the male joins her in the bottom of the redd, she releases some of her eggs and the male fertilizes them.  The male then departs, while the female digs on the upstream edge of the redd, which covers the eggs while she excavates a new depression. When this depression is ready, she releases pheromones and repeats the process of laying eggs while a male fertilizes them. Each female will engage in 5-7 egg-laying episodes before she has deposited all of her 3000 to 5000 eggs in the gravel. When she completes her task, all of the eggs will be covered by 12-16 inches of gravel, which provides protection for the eggs. After spawning is completed, all Pacific salmon die; this final sacrifice provides essential nutrients for the food chain that will support the juvenile salmon during their time rearing in freshwater. Life Cycle of Spring Chinook on the Cle Elum River Video In December, the eggs hatch. The alevins, or sac fry, stay in the gravel and gradually absorb the orange-colored yoke sac. The fry remain in the gravel through the winter and into the spring. In May, when the water is warming up and food production in the river accelerates, the yolk is completely absorbed and the fry have to emerge from the gravel and begin to feed on their own. Spring Chinook spend a full year in freshwater before migrating to the ocean the following spring. Instead of swimming to the ocean, they ride the high water, or “freshet”, created by the melting mountain snow-pack. This high water is equivalent to a human catching a bus and riding to the mouth of the Columbia River. “The Bus” Catching the High Water Video Research results indicate that the survival of spring Chinook in the Yakima Basin from the egg phase to migrating to the ocean as smolts averages approximately 5%. When they return, the surviving adults will spawn in the same area of the river that they themselves came from. The ability to locate their natal gravel is one of the marvels of the natural world.

The male then departs, while the female digs on the upstream edge of the redd, which covers the eggs while she excavates a new depression. When this depression is ready, she releases pheromones and repeats the process of laying eggs while a male fertilizes them. Each female will engage in 5-7 egg-laying episodes before she has deposited all of her 3000 to 5000 eggs in the gravel. When she completes her task, all of the eggs will be covered by 12-16 inches of gravel, which provides protection for the eggs. After spawning is completed, all Pacific salmon die; this final sacrifice provides essential nutrients for the food chain that will support the juvenile salmon during their time rearing in freshwater. Life Cycle of Spring Chinook on the Cle Elum River Video In December, the eggs hatch. The alevins, or sac fry, stay in the gravel and gradually absorb the orange-colored yoke sac. The fry remain in the gravel through the winter and into the spring. In May, when the water is warming up and food production in the river accelerates, the yolk is completely absorbed and the fry have to emerge from the gravel and begin to feed on their own. Spring Chinook spend a full year in freshwater before migrating to the ocean the following spring. Instead of swimming to the ocean, they ride the high water, or “freshet”, created by the melting mountain snow-pack. This high water is equivalent to a human catching a bus and riding to the mouth of the Columbia River. “The Bus” Catching the High Water Video Research results indicate that the survival of spring Chinook in the Yakima Basin from the egg phase to migrating to the ocean as smolts averages approximately 5%. When they return, the surviving adults will spawn in the same area of the river that they themselves came from. The ability to locate their natal gravel is one of the marvels of the natural world.

Return to Natural Production Video The best basin to do significant restoration of natural production in the Columbia River system is in the Yakima Basin. To be sure, we have challenges in water management and flows. But, if we provide a large quantity of water in the Yakima River basin dedicated to salmon restoration, there is no reason we can’t produce greatly increased salmon runs. There is a lot of potential in this Basin but we must have a vision as big as the potential. Yakima Basin Low Flow Problems Video We can’t maintain agriculture at the current acreage, provide that acreage with sufficient water during droughts, and produce greatly increased salmon runs with the water supplies from the Yakima Basin. There is only one place to get the large quantity of water to provide for both irrigation and fish restoration, and that is from the Columbia River. How to Save Agriculture and Fish in the Yakima Basin Video Bring water out of the Columbia River and put it in the Roza and Sunnyside canals and then unhook those districts from the Yakima River. The Yakima Basin water supply formally used by those two districts could then be utilized to support salmon restoration throughout the basin, while still providing the water needed for irrigation from the Columbia River. In addition, we need to build passage at the storage dams, and purchase, protect, and restore floodplain and riparian habitat. Central to this restoration strategy is the restoration of the 100 miles of the lower Yakima River. We had a vision 30 years ago; what was once only a vision, a dream, is not reality. We can go see this new reality, we can stand on it; most importantly, we can watch it spawn in the river. We have constructed fish ladders and fish screens throughout the Yakima Basin; we have modified water management to protect redds and aid migrating fish. Yakima Basin Flip Flop Process for Fish Video  We now need to move on to a new vision, so that 30 years from now that, too, will be reality. That vision is a secure and prosperous agricultural economy, and vastly increased salmon runs in the Yakima Basin. That vision requires new solutions and bold approaches. The idea of pumping water out of the Columbia River is not new. It is already being done on the Umatilla River, and planning to implement a similar project in the Walla Walla River is well underway. The Umatilla Project has been successful in supplying the irrigation water needed while providing water for fish. In addition, pumping out of the Columbia River is the probable solution to declining groundwater in the Odessa area. Pattern of Water Exchange in River Basins Video

We now need to move on to a new vision, so that 30 years from now that, too, will be reality. That vision is a secure and prosperous agricultural economy, and vastly increased salmon runs in the Yakima Basin. That vision requires new solutions and bold approaches. The idea of pumping water out of the Columbia River is not new. It is already being done on the Umatilla River, and planning to implement a similar project in the Walla Walla River is well underway. The Umatilla Project has been successful in supplying the irrigation water needed while providing water for fish. In addition, pumping out of the Columbia River is the probable solution to declining groundwater in the Odessa area. Pattern of Water Exchange in River Basins Video  Twenty years from now climate change is really going to be a driver of our water supply in the Yakima Basin. It will affect either the timing or total amount, or both. The water exchange project with the Columbia River would allow us to meet this unprecedented challenge without causing economic and social upheaval. Climate Change Video Sockeye above Lake Cle Elum Video The choice is ours: Boldly prepare for the future, or be prisoners of the future. Control our own destiny, or have our destiny determined by outside forces and decisions. By Bob Tuck Yakima Herald-Republic Editorial Board This editorial appears in the Yakima Herald-Republic on April 12, 2009. Study stymies new storage, but need for water remains It looks like those involved in the search for water enhancement in the Yakima River Basin have finally agreed on one thing: We don’t need another endless cycle of studies. “Since the 1980s there’s been no end to this stuff,” said Jerry Kelso, area manager for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in Yakima. “There needs to be an end.” We couldn’t agree more. Kelso’s pronouncement came a week ago after the bureau ended a five-year, $18 million study that concluded none of the suggested new water storage projects — from a tiny reservoir off the Yakima River to the behemoth Black Rock reservoir east of Yakima — are worth pursuing. However, that doesn’t mean the Yakima River Basin has an adequate water supply to meet the needs of irrigators, cities and migrating fish — now or into the future. Far from it. Water experts predict worsening conditions due to climate changes will lead to increased threats of drought. Within the next 50 years, the region could be experiencing eight drought years out of every 10. Right now, California is facing critical water shortages with farmers taking more than 1 million acres out of production. For the Yakima Valley, that type of flexibility is not possible. Tree fruits dominate our ag crops. When a tree dies in a drought, a return to production takes years, not to mention vast new expenditures. The result would be economic chaos. Though the bureau has said the options for new storage are not worth pursuing, that also doesn’t mean the debate has ended, especially with respect to Black Rock. The bureau essentially gave the proposed 1.6 million-acre-foot reservoir a stay of execution. The controversial project has at least as many pluses going for it as it does minuses. Critics say its ballooning estimated cost of construction, now projected at $4 billion-plus, is far too much and that its return on each dollar invested of 13 cents is way too low. Then there’s the ticking time bomb of predicted seepage, which could speed pollutants to the Columbia River from the Hanford nuclear reservation to the east. Proponents counter by saying the bureau’s analysis of costs is flawed and does not calculate the value of such amenities as recreation. They also say Black Rock is the only proposal on the table that satisfies the three-pronged mandate handed down by Congress when it authorized studies for the Yakima basin: water for fish, water for people and water for irrigators. The project would draw water from the Columbia River when it has excess water, pump it uphill and store it behind a 600 foot-high dam about 30 miles east of Yakima. That would allow greater flows in the Yakima River by providing irrigation water for area crops. But added storage is only one aspect of a realistic solution. Better water conservation and fish habitat, along with improved fish passage at dams in the upper reaches of the Yakima River, must also be in play. Bringing all of these elements together will be the goal of one last study by the state Department of Ecology. The department is attempting to determine the best alternative to meet the most needs. Then comes the crucial effort to get all of the competing interests in the basin — from the Yakama Nation to junior water rights holders within the Roza Irrigation District — at the same table with the sole purpose of getting a thumbs up on a solution. That’s a tall order, but it is not out of reach. Certainly those leading the Yakima Basin Storage Alliance have done the right thing at this time by agreeing to step back after years of guiding the discussion. The alliance is looking to the elected commissioners from the three-county basin to shoulder that new leadership role. This move should entice the Yakama Nation to join in the discussion — which is critical if any legislation is to eventually be presented to Congress for funding. We suggest taking one additional step. Why not invite Gov. Chris Gregoire and get her involved in a leadership role? The governor once oversaw the Department of Ecology and served as the state’s attorney general as well. You couldn’t ask for better qualifications, and they will be needed to get agreement from such a diverse group of water users, not to mention environmentalists. Doing nothing is not an option. The future of the Yakima Valley demands action. And the sooner the better. * Members of the Yakima Herald-Republic editorial board are Michael Shepard, Bob Crider, Barbara Serrano, Spencer Hatton and Karen Troianello. Dr. Jack Stanford Visits Yakima

Twenty years from now climate change is really going to be a driver of our water supply in the Yakima Basin. It will affect either the timing or total amount, or both. The water exchange project with the Columbia River would allow us to meet this unprecedented challenge without causing economic and social upheaval. Climate Change Video Sockeye above Lake Cle Elum Video The choice is ours: Boldly prepare for the future, or be prisoners of the future. Control our own destiny, or have our destiny determined by outside forces and decisions. By Bob Tuck Yakima Herald-Republic Editorial Board This editorial appears in the Yakima Herald-Republic on April 12, 2009. Study stymies new storage, but need for water remains It looks like those involved in the search for water enhancement in the Yakima River Basin have finally agreed on one thing: We don’t need another endless cycle of studies. “Since the 1980s there’s been no end to this stuff,” said Jerry Kelso, area manager for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in Yakima. “There needs to be an end.” We couldn’t agree more. Kelso’s pronouncement came a week ago after the bureau ended a five-year, $18 million study that concluded none of the suggested new water storage projects — from a tiny reservoir off the Yakima River to the behemoth Black Rock reservoir east of Yakima — are worth pursuing. However, that doesn’t mean the Yakima River Basin has an adequate water supply to meet the needs of irrigators, cities and migrating fish — now or into the future. Far from it. Water experts predict worsening conditions due to climate changes will lead to increased threats of drought. Within the next 50 years, the region could be experiencing eight drought years out of every 10. Right now, California is facing critical water shortages with farmers taking more than 1 million acres out of production. For the Yakima Valley, that type of flexibility is not possible. Tree fruits dominate our ag crops. When a tree dies in a drought, a return to production takes years, not to mention vast new expenditures. The result would be economic chaos. Though the bureau has said the options for new storage are not worth pursuing, that also doesn’t mean the debate has ended, especially with respect to Black Rock. The bureau essentially gave the proposed 1.6 million-acre-foot reservoir a stay of execution. The controversial project has at least as many pluses going for it as it does minuses. Critics say its ballooning estimated cost of construction, now projected at $4 billion-plus, is far too much and that its return on each dollar invested of 13 cents is way too low. Then there’s the ticking time bomb of predicted seepage, which could speed pollutants to the Columbia River from the Hanford nuclear reservation to the east. Proponents counter by saying the bureau’s analysis of costs is flawed and does not calculate the value of such amenities as recreation. They also say Black Rock is the only proposal on the table that satisfies the three-pronged mandate handed down by Congress when it authorized studies for the Yakima basin: water for fish, water for people and water for irrigators. The project would draw water from the Columbia River when it has excess water, pump it uphill and store it behind a 600 foot-high dam about 30 miles east of Yakima. That would allow greater flows in the Yakima River by providing irrigation water for area crops. But added storage is only one aspect of a realistic solution. Better water conservation and fish habitat, along with improved fish passage at dams in the upper reaches of the Yakima River, must also be in play. Bringing all of these elements together will be the goal of one last study by the state Department of Ecology. The department is attempting to determine the best alternative to meet the most needs. Then comes the crucial effort to get all of the competing interests in the basin — from the Yakama Nation to junior water rights holders within the Roza Irrigation District — at the same table with the sole purpose of getting a thumbs up on a solution. That’s a tall order, but it is not out of reach. Certainly those leading the Yakima Basin Storage Alliance have done the right thing at this time by agreeing to step back after years of guiding the discussion. The alliance is looking to the elected commissioners from the three-county basin to shoulder that new leadership role. This move should entice the Yakama Nation to join in the discussion — which is critical if any legislation is to eventually be presented to Congress for funding. We suggest taking one additional step. Why not invite Gov. Chris Gregoire and get her involved in a leadership role? The governor once oversaw the Department of Ecology and served as the state’s attorney general as well. You couldn’t ask for better qualifications, and they will be needed to get agreement from such a diverse group of water users, not to mention environmentalists. Doing nothing is not an option. The future of the Yakima Valley demands action. And the sooner the better. * Members of the Yakima Herald-Republic editorial board are Michael Shepard, Bob Crider, Barbara Serrano, Spencer Hatton and Karen Troianello. Dr. Jack Stanford Visits Yakima Dr. Jack Stanford will be in Yakima September 24 to tell us his vision of how to restore 1,000,000 salmon and steelhead to the Yakima River Basin . He believes there is no better place to do so in the lower 48 States than the Yakima . He is an expert in Limnology (River Ecology) and river restoration who has worked extensively with rivers in the Northwest and around the world; in British Columbia , Russia , Europe and South America . He is the M. Bierman Professor of Ecology, at the University of Montana , where he is the Director of the Flathead Lake Biological Station as well as a member of the National Academy of Science, and other organizations.

Dr. Jack Stanford will be in Yakima September 24 to tell us his vision of how to restore 1,000,000 salmon and steelhead to the Yakima River Basin . He believes there is no better place to do so in the lower 48 States than the Yakima . He is an expert in Limnology (River Ecology) and river restoration who has worked extensively with rivers in the Northwest and around the world; in British Columbia , Russia , Europe and South America . He is the M. Bierman Professor of Ecology, at the University of Montana , where he is the Director of the Flathead Lake Biological Station as well as a member of the National Academy of Science, and other organizations.

See Press Releases below.

Study underestimates value, urgency of Black Rock Reservoir project

Yakima River Basin Water Storage Feasibility Study Draft Planning Report/Environmental Impact Statement http://www.usbr.gov/pn/programs/storage_study/reports/eis/draft-pr-eis.pdf

Yakama Nation Review Article Solving the Water Shortage in the Yakima Basin